Cars, sheep and large landowners: winning trio in the Hautes-Alpes (before hangover)

2. Summers of sheep

In the Hautes-Alpes in southern France as in other parts of the world, one can always focus on environmental and social accomplishments: the adequate protection of certain wildlife species; the welcoming of foreign migrants within organized groups and families; the efforts made by small farmers and consumers to sustain organic farming; the collection and treatment of compost at the municipal level; etc. But the scope of these accomplishments remains limited. They are never part of a lifestyle that could be considered truly balanced from economic and environmental standpoints. We don’t need to impose this lifestyle on others, but we need to be able to lead it without obstacles put in our way by hateful opponents. Prevailing trends, namely the immense social inequity rooted in our economic and legal systems and environmental mismanagement, stand in our way. In order to liberate people who want it from these scourges, we have to identify and explain them as clearly as possible. It helps us minimize cooperation with the insane established order and implement solutions consistent with both our needs as human beings and the needs of our environment. These are the two goals of this series of articles on the Hautes-Alpes.

1. Driving safely towards global warming

3. The lowness of large landowners on top of the Hautes-Alpes (courtesy of French legislators)

Subscribe to my newsletter

Buy PDF of part 2 (€1.00)

Buy eBook (.epub and .mobi) of part 2:

Hautes-Alpes - Part 2 (6/2018)

IN THE HAUTES-ALPES, THERE MIGHT BE AS MANY SHEEP LOVERS AS THERE ARE CAR LOVERS. Both types of lovers share similar ideas. For them, the environment is secondary at best. The economy always comes first. Sometimes, the environment is relegated much farther away in their list of priorities.

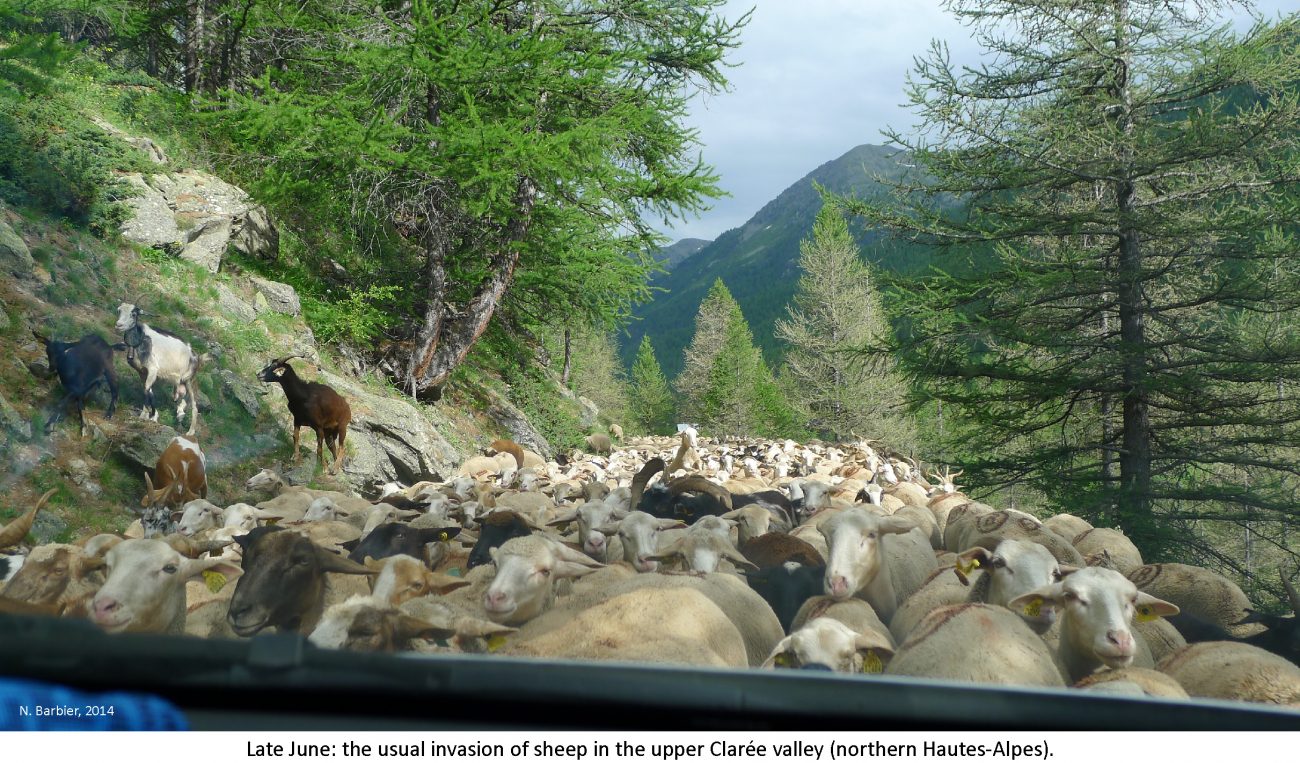

In 2015, the sheep population in the département of the Hautes-Alpes reached 260,000. It is twice the human population. Less than 600 sheep producers own the 260,000 heads. During the summer, they graze on 200,000 hectares of alpine pastures which include sparse trees in some areas. These pasture are generally located between 1,800 and 3,000 meters above sea level. Sheep spare neither the Natura 2000 areas[1] nor the Ecrins national park. Every summer, sheep producers take over 36 percent of the Hautes-Alpes total area and occupy three-quarters of its alpine meadows. In the Région Sud, which includes six départements stretching from the Mediterranean sea in the south to the Hautes-Alpes in the north, sheep production is made up of 80 percent of lambs for slaughter (Agreste, 2010, p.3 ; Chambres d’agriculture PACA, 2017 [a] ; MRE, 2012 et 2013 ; Natura 2000 Hautes-Alpes ; Parc national des Ecrins, 2018 ; Préfet des Hautes-Alpes, 2013).

The industrial-scale sheep production is only partly « local ». In the French Alps as a whole, only one-third of herds of sheep stay in alpine pastures located within their municipal area of origin in the summer. Another third comes from another municipal area within the département. The remaining third originates from another département (Irstea et al., 2016).

In Haut-Alpin country, 77 percent of the areas grazed by the 260,000 sheep belong to municipalities. Generally, these municipalities roll out the red carpet for them by leasing alpine meadows to sheep producers at a friendly price. It can be as low as 8 euros per hectare and per year. Let’s take a regional example: in the southern French Alps, sheep producers pay 3 euros per sheep so that 1,300 sheep could stay in alpine pastures for the summer (Agreste, 2010, p.3 ; Chambres d’agriculture PACA, 2018 [a] et 2017 [b] ; Irstea et al., 2016).

At the beginning of each summer, a good part of wild animals run away from alpine meadows when the sheep rush onto them (photo 4). Repeated every year, this tradition has upset countless ecosystems.

Photo 4

500 sheep grazing for 14 hours produce about one ton of feces. The damage they cause vary according to their concentration on the land and the type of terrain. Sheep love to wander on ridges, through bushes or in the middle of screes. In these different terrains, they degrade both the soils and vegetation. Sheep are also fond of wetlands, which are more fragile, especially near streams (photos 5). Even in national parks, streams are commonly not protected by fences (Lapeyronie et Moret, 2007, p.206-208).

Photos 5

Everywhere they go in alpine pastures or in the subalpine and montane[2] areas below, sheep damage ecosystems to varying degrees, depending on location (photos 6):

- They reduce biodiversity, remove certain plant species and contaminate quite a few wild animal species.

- They pollute both groundwater and surface water.

- They lead to excess nitrogen on grazing land.

- Because of their trampling, they cause soil compaction, which in turn diminishes both the soil’s capacity to hold water and the exchange of nutrients between soil and plants.

- When sheep remove plants or denude soils, it also results in erosion. As a consequence, soils lose both nutrients and organic materials (Lapeyronie et Moret, 2007, p.206-208 ; Monbiot, 2014, p.70, 210 ; Wilshire et al., 2008, p.80-81).

Photos 6

Sheep production keeps its place within the Hautes-Alpes. But if we want to respect the ecosystems of alpine meadows, then sheep producers should not be allowed to appropriate huge areas during the summer. If current alpine pastures for sheep were reduced by 80 percent, 40,000 hectares would still be available for them. Such a reduction in size would bring about four ecological benefits:

- A better interannual pasture rotation. As a consequence, environmental damages would be considerably reduced.

- Pastures would be banned in the most fragile alpine ecosystems.

- Wetlands would be closed to sheep everywhere using fences (which can be taken to pieces) in combination with water troughs. Yes, more fences and water troughs remain a highly uncertain progress for the 21st century in the Hautes-Alpes.

- Areas cleared of sheep could be reclaimed by wildlife.

Contrary to what lots of people believe, sheep production is by no means a major industry in the Hautes-Alpes. This sector employs between 1,500 and 1,800 people including many seasonal workers. It is twelve times less than intermediate professions[3] for instance. The yearly value of sheep production is approximately 20 million euros (of which 5 million are subsidies). This represents only 12 percent of the total agricultural production in the Hautes-Alpes. Moreover, in 2014, only 7 percent of flocks of sheep were considered part of organic agriculture (Insee, 2016 [a] ; Agreste PACA, 2016, p.13, 25, 34).

A personal experience can explain, at least in part, why sheep production is the number one priority on most alpine meadows in the southern French Alps. That priority has been protected through different forms of violence spread by most sheep producers and local elected officials. On May 23, 2018, I laid out a touristic and environmental project before three local officials. The director of the tourism agency for the Guillestrois and Queyras region (eastern Hautes-Alpes), the mayor of Ristolas (eastern Queyras) Christian Laurens and a deputy mayor for the municipality of Guillestre (Dominique Moulin) were present. My project would consist in creating ten or so campgrounds, each of which could welcome about forty people. They would be strategically placed in an area stretching over more than 1,200 km² (Guillestrois, Pays des Ecrins, Queyras). The campgrounds would be located along attractive trails and paths between 1,000 and 2,500 meters above sea level and several kilometers from any inhabited place.

Up there, hikers and mountain bikers could enjoy the scenery and use some equipment made available for them at a reasonable price. It would include:

- Tents and sleeping pads in storage lockers.

- Bicycle racks and anti-theft devices.

- Solar showers.

- Dry toilets.

- Roofed picnic tables, etc.

For one night, a mountain biker would spend 8 euros for the access to picnic tables and dry toilets, the renting of a tent for two persons, a sleeping pad, a bicycle rack (plus the anti-theft device) and a solar shower.

Importantly, all campgrounds would be set up on municipal lands. In order to attract as many people as possible, most of them would be built in alpine meadows and a few others in lower elevation areas (photo 7).

Photo 7

The director of the tourism agency (devoid of decision-making authority) said that my project was innovative. The two elected officials rejected it. They did not oppose my project due to issues about security, water management for solar showers, campfires or even funding. They know that funding is never the easy part for this kind of project, but if twenty municipalities fund it together, this obstacle would be quickly overcome.

The main reason why elected officials said no to my project is different. In short, they give absolute priority to sheep production on virtually all alpine, subalpine and montane meadows. Period. Upon completion of my project, sheep producers would have to share tiny portions of these lands. The two elected officials were adamantly opposed to this. The mayor of Ristolas’ behavior made me think of elected officials in the American West that I interviewed for a documentary film a few years ago. As if this mayor was ready to call in policemen and armed sheep producers to make it impossible. If the deputy mayor of Guillestre’s behavior was somewhat less hostile, he nonetheless approved the mayor’s words.

These two elected officials vaguely suggested that I should limit my project to extensions for existing campgrounds. But in doing so, my project would lose most of its ecological, economic and social interests. There would be almost nothing left of it but more economic gains for private and municipal campgrounds.

I have not received a single positive response from other mayors in Queyras and the Pays des Ecrins I had written to. In the end, I came up against three forms of violence fostered by the alliance made of sheep producers and local elected officials. In the French Alps, most of them routinely use these forms of violence:

- Environmental violence: sheep producers and elected officials defend all current excesses of sheep production, never mind if those excesses cause extensive deterioration of alpine, subalpine and montane meadows.

- Territorial violence: they retain vast expanses of land for a discriminatory use that both excludes others and is rather weak in terms of regional economic impact.

- Social violence: they thwart projects that are promising from ecological, economic and social standpoints. My project could create meaningful jobs. It would be open to tourists who don’t have much money. It would benefit a lot of local businesses (e.g., grocery stores, restaurants, sports shops). With effective communication, municipalities could also draw substantial revenues six or seven years after the project is launched. Finally, because campgrounds welcome only hikers and mountain bikers, this project would generate virtually no emission of CO2 gases aside from the necessary light maintenance of campgrounds.

Local elected officials worry about something else when they look at projects like this. They keep a look-out for any kind of competition on the juicy rental housing market for tourists. They seem to worry for both electoral reasons (i.e., families who own houses or apartments and rent them to tourists) and economic reasons (in favor of rich tourists first and foremost). So they seek a tourism development that does not change sheep production at all, always lures the upper class and is most likely to bring quite a lot of revenues.

The Alta Peyra luxury hotel in Saint Véran is a case in point (photos 8). The big investments in snowmaking equipment is another (e.g., 2 million euros in Montgenèvre, 2.2 million in Risoul, 4.9 million in Orcières). Housing complexes for tourists, such as the Sporting complex in Serre-Chevalier (400 beds for 11.2 million euros) in order to « meet the new quality standards », is yet another. These types of projects fit well in the regional economic direction (Caisse des dépôts, 2015 ; TPBM, 2017).

Photos 8

I made some calculations related to the profitability of my project. With an occupancy rate in the campgrounds of 40 percent from May to October, it would bring in 2 million euros over ten years. During this period, it should cost 1.5 million euros. So the net revenues could top 500,000 euros after ten years, and more during the ten following years. If twenty municipalities agreed to fund it, each of them would spend no more than 7,500 euros per year. 7,500 euros is 4 percent of the price for a 100 square-meter house around here. What’s more, the ten campgrounds would cover something like 20 hectares or 0.01 percent of the total area used by sheep in the Hautes-Alpes’ alpine pastures every summer (MeilleursAgents.com, 2018).

In concert with the French state, most sheep producers and local elected officials (of course legitimized by voters) get their act together to remain the violent protectors of a socially detrimental, economically senseless and environmentally harmful business in most alpine, subalpine and montane meadows.

Sources

Agreste PACA, 2016. Mémento de la statistique agricole. 19/5/2018.

Agreste, 2010. Portrait agricole : les Hautes-Alpes. 16/5/2018.

Caisse des dépôts, 2015. Hautes-Alpes : développer l’immobilier de montagne, une 1re pierre et une étude. 30/5/2018.

Chambres d’agriculture PACA, 2018 [a]. Locations des terres agricoles. 16/5/2018.

Chambres d’agriculture PACA, 2017 [a]. Productions animales. 16/5/2018.

Chambres d’agriculture PACA, 2017 [b]. Elevage ovin. Une filière dynamique dans un contexte socio-économique difficile. 31/5/2018.

European Commission, 2017. Natura 2000. 22/6/2018.

Insee, 2016 [a]. Dossier complet – Département des Hautes-Alpes (05) : FAM T2 – Ménages selon la catégorie socioprofessionnelle de la personne de référence en 2014. 19/5/2018.

Irstea et al., 2016. 3000 alpages/estives dans le massif des Alpes. 16/5/2018.

Lapeyronie P. et Moret A., 2007. Protection des troupeaux et impacts environnementaux. In Garde L. : Loup – Elevage : s’ouvrir à la complexité. Eds. CERPAM. pp.202-211. 16/5/2018.

MeilleursAgents.com, 2018. Prix immobilier à Guillestre (05600). 8/6/2018.

Monbiot G., 2014. Feral: rewilding the land, sea and human life. Penguin Books. 317 p.

MRE, 2013. Projet « élevage 2020 ». 16/5/2018.

MRE, 2012. La filière ovine en PACA. 16/5/2018.

Natura 2000 Hautes-Alpes, 2012. Natura 2000 Hautes-Alpes. 16/5/2018.

Parc national des Ecrins, 2018. Les alpages. 16/5/2018.

Préfet des Hautes-Alpes, 2013. L’agriculture haut-alpine. 16/5/2018.

TPBM, 2017. Les stations investissent massivement dans la neige de culture. 30/5/2018.

Wilshire H. et al., 2008. The American West at Risk. Oxford University Press. 619 p.

ventdouxprod 2018, all rights reserved

Footnotes

[1] « Natura 2000 is a network of core breeding and resting sites for rare and threatened species, and some rare natural habitat types which are protected in their own right. It stretches across all 28 EU countries, both on land and at sea. The aim of the network is to ensure the long-term survival of Europe’s most valuable and threatened species and habitats, listed under both the Birds Directive and the Habitats Directive » (European Commission, 2017).

[2] The montane area or zone is located just below the subalpine area, usually between 500 and 1,600 meters above sea level.

[3] Intermediate professions are usually categorized between executives and employees (e.g., nurses, supervisors, teachers, technicians).